- Home

- Hilary Mantel

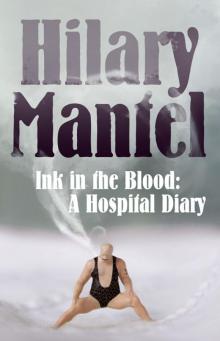

Ink in the Blood

Ink in the Blood Read online

Ink in the Blood

A Hospital Diary

HILARY MANTEL

Contents

Ink in the Blood

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Ink in the Blood

Three or four nights after surgery – when, in the words of the staff, I have ‘mobilised’ – I come out of the bathroom and spot a circus strongman squatting on my bed. He sees me too; from beneath his shaggy brow he rolls a liquid eye. Brown-skinned, naked except for the tattered hide of some endangered species, he is bouncing on his heels and smoking furiously without taking the cigarette from his lips: puff, bounce, puff, bounce. What rubbish, I think: actually shouting at myself, but silently. This is a non-smoking hospital. It is impossible this man would be allowed in, to behave as he does. Therefore he’s not real, and if he’s not real I can take his space. As I get into bed beside him, the strongman vanishes. I pick up my diary and record him: was there, isn’t any more.

This happened in early July, 2010. I had surgery on the first of the month, and was scheduled to stay in hospital for about nine days. The last thing the surgeon said to me, on the afternoon of the procedure: ‘For you, this is a big thing, but remember, to us it is routine.’ The operation was to relieve a stricture in my bowel, before it closed completely and created an emergency. But though we had used the latest scans in preparation, neither patient nor doctor could imagine the damage left by the endometriosis for which I’d had surgery 30 years before. Organs were stuck together, pulled out of shape. It took six hours to disentangle the wreckage. When I woke up, my surgeon was standing at the end of the trolley in the recovery room, grey and shrunken as if a decade had passed. He had expected to be home for dinner. And now look!

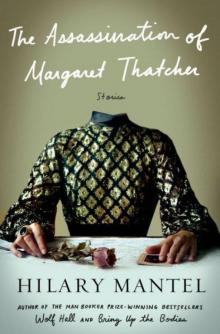

Hospital talk is short and exclamatory. Oops! Careful! Nice and slow! Oh, dear! Did that hurt? But the night after the surgery, I felt no pain. Flighted by morphine, I thought that my bed had grown as wide as the world, and throughout the short hours of darkness I made up stories. I seemed to solve, that night, problems that had bedevilled me for years. Take just one example: the unwritten story called ‘The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher’. I had seen it all, years ago: the date and place, the gunman, the bedroom behind him, the window, the light, the angle of the shot. But my problem had always been, how did the Armalite get in the wardrobe?

Now I saw that it just grew there. It was planted by fantasy. If a whole story is a fantasy, why must logic operate within it? The word ‘planted’ started another story, called ‘Chlorophyll’. By morning, I had the best part of a collection. But when I sat up and tried to write them down, my handwriting fell off the lines. I kept trying to fish it up again, untangle the loops and whorls and get them back to the right of the margin, and when I think of my efforts then, I think of them in the present tense, because pain is a present-tense business. Illness involves such busywork! Remembering to breathe. Studying how to do it. Plotting to get your feet on the floor, inching a pillow to a bearable position. First move your left foot. Then your other foot, whatever they call it . . . any other foot you’ve got. Let us say you’re swaying on your feet and sweating, you think you might fall down or throw up – you have to rivet your attention to the next ten seconds. After the crisis is over, time still behaves oddly. It takes a while for the hour to stretch out in its usual luxurious fashion, like unravelling wool. Until you are cool, settled and your vital signs good, time snaps and sings like an elastic band.

When I write my diaries I talk to myself with an inward voice. For the next week I am conscious that my brain is working oddly. Imagine you were creating all your experience by writing it into being, but you were forced to write with your wrong hand; you would make up for the slow awkwardness by condensing phrases, like a poet. In the same way, my life compresses into metaphor. When I sit up and see the wound in my abdomen, I am pleased to see that it has a spiral binding, like a manuscript. On the whole I would rather be an item of stationery than be me. It is as if my thoughts are happening not inside my head but outside me in the room. A film with a soundtrack is running on my right side. It keeps me busy with queries based on false premises. ‘Is it safe if I drink this orange juice?’ But I blink and the orange juice isn’t there. Therefore I study reality carefully, the bits of it within reach. For a while I think I have grown a new line on one of my hands, a line unknown to palmistry. I think perhaps I have a new fate. But it proves to be a medical artefact, a puckering of the skin produced by one of the tubes sewn in to my wrist. We call those ‘lines,’ too. The iambic pentameter of the saline stand, the alexandrine of the blood drain, the epidural’s sweet sonnet form.

Within a few days, the staff are tampering with my spiral binding when the whole wound splits open. Blood clots bubble up from inside me. Over the next hours, days, nurses speak to each other in swift acronyms, or else form sentences you might have heard in Haworth: ‘Her lungs are filling up.’ But I have undentable faith in my own body. When I am told I need a blood transfusion, I plead, ‘Let’s give it 24 hours and see.’ I have never been accepted as a blood donor, and I don’t like the idea of a debt. When the blood comes, the stranger’s precious blood, it leaks everywhere from the cannula on my neck, which needs to be taken out and resewn. The night sister looks meaningfully at the vampire’s kiss and says, ‘Another two of those wounds would do it.’ Finish me off, she means. She is real but I accept her words are not. A hallucination has to be gross before I can pick it.

My internal monologue is performed by many people – nurses and bank managers are to the fore. There is a breathless void inside me, and I think it needs to be filled. I should put money in it, I think. Like a cash machine in reverse, notes slotting between my ribs. Certain items are taken away – the drain that takes blood from my side, a bridle that feeds me oxygen – but they are never taken far enough away, they easily come back. I clamp a smile on my face and drift. I have a switch I can press for ‘patient controlled analgesia’. But the staff seem uneasy about giving up control over my pain. Some say I am pressing the button too often, some say too seldom. I want to please them so I try and make my pain to their requirements.

Illness strips you back to an authentic self, but not one you need to meet. Too much is claimed for authenticity. Painfully we learn to live in the world, and to be false. Then all our defences are knocked down in one sweep. In sickness we can’t avoid knowing about our body and what it does, its animal aspect, its demands. We see things that never should be seen; our inside is outside, the body’s sewer pipes and vaults exposed to view, as if in a woodcut of our own martyrdom. The whole of life – the business of moving an inch – requires calculation. The suffering body must shape itself around the iron dawn routine, which exists for the very sick as well as the convalescent: the injection in the abdomen, pain relief, blood tests as needed, then the long haul out of bed, the shaking progress to the bathroom, the awesome challenge of washcloth and soap.

This is a small private hospital, clean and unfancy, set in the sprawling campus of a vast public hospital of which I have experience, and have reason to distrust and detest. I feel guilty, God knows, about all sorts of things, but not about buying myself a private room. The staff looking after me are the same people who would be working at the larger institution, but they are less rushed and so more considerate. It’s usual in talking about health services to say that the system needs all sorts of reforms but the workers are wonderful. I think that the workers are as apt to fail as the system is, though the staff here are about as good as busy nurses can be. Some people, on a hospital ward or anywhere else, always do what they say they’ll do, and others just don’t; to them, promises are ju

st negotiating ploys, and the time on the clock is secondary to some schedule of their own. Some can imagine being in pain, and some don’t want to. A single extra minute to settle a patient comfortably can mean the difference between a neutral experience and an experience of slowly building misery. Some take the human body to be made of flesh, some of jointed metal. A polite radiographer bends my arm back over the side of a trolley so that it feels as if he’s trying to break it. And I too think of my body as consisting of some substance that I can split apart from myself, and hand over to the professionals, while I take an informed interest in what they do to it. Far from being isolating, my experience is collaborative. The staff are there to reassure me, and I am there to reassure them; in this way we shield each other from an experience of darkness. One day soon after the surgery I vomit green gunk. ‘Don’t worry!’ I exclaim as I retch. ‘It will be fine! It’s just like The Exorcist,’ I say, before anyone else can.

And so I spin away, back into the 1970s; I am easily parted from the present day. I remember the cinema queues and the evangelicals working their way along the jeering lines, trying to dissuade us from going in. I wish I had been dissuaded. ‘What were those flickering skulls about?’ I asked as we filed out. (Apart from those, I thought the film quite true to life.) No one else I knew saw the skulls, not then, though by now it seems everybody has. If you have a million years to spare, you can follow the internet discussions on what ‘quasi-subliminal’ images may or may not have been embedded by the film-makers, but when I was young I would always reliably see what was almost not there; when I was a student, earning a little money by being an experimental subject for trainee psychologists, I did many dull routines involving word association and memory tricks, but what I remember best is the flicker of screens with letters I could just read, and being asked, disapprovingly, ‘How do you do that?’ This was not a professional question, but an aggrieved, human one; people suspect you are sneaking some mean advantage. No doubt I have lost this ability now, if ability is what you call it. It’s something you’d think age would wither. But given my record with the vaporous, I am not as surprised as some would be, when in the hospital I blink and life flits sideways. The second world, the whirl of activity on my right-hand side, wakes up just after the first world, so that for a moment, as I push back the bedcovers, I am united, I speak with one voice. A second later, reality has fallen into halves. In my notebook, hour by hour, I record the hallucinations and my own scathing comments on them. But the footnotes are no more sensible than the main text, since while criticising and revising I am still hallucinating. What is this preposterous stuff, I demand of myself, about getting the nave of the church measured? ‘As if,’ I write, ‘this were not a hospital, but a Jane Austen novel with a wedding at the summit?’

A voice from the secondary world rebukes me for thinking so little of my real father, whom I never saw after I was 11. ‘Why, he sold tickets to make brickets from granite. He collected clothes and kit for historical re-enactments.’ I do not mention my two worlds to the staff, as they have enough to do and it seems tactless. Most of my preoccupations are literary or religious, so they seem an elitist pursuit, and for many of my nurses, English is not their first language, nor Christianity their religion. ‘The existing vicar,’ a voice tells me, ‘will go to a smaller parish somewhere.’ At once the existing vicar bobs into view, followed by an anguished Muslim father, who pleads to know, ‘What are the chances of her losing her honour?’ The vicar explains loftily that he and his clerical colleagues do not exist to answer that sort of question. ‘They do not believe that honour lies in fearful nasties.’ Sorry, I write, I misheard: that should read ‘fearful chastity’. A hooded youth approaches me on the street, holding up a plucked chicken. ‘You give me this bird,’ he complains, ‘and this bird were gay.’

There is no obvious reason for voices and visions. My temperature is near normal and my pain relief is the usual moderate regime. Later the hallies, as I think of them, become less threatening, but more childish and conspiratorial. I close my eyes and they begin to pack my belongings into a pillow case, whispering and grinning. One sharp-faced dwarfish hally pulls at my right arm, and I drive her off with an elbow in her eye. After this they are more wary of me, intimidated. I see them slinking around the door frame, trying to insinuate themselves. The staff are concerned that I don’t cough, then that I cough too much. In soothing nurse-talk they smooth symptoms away. ‘I have a raging thirst,’ I say. ‘Ah, you are a lit-tul bit thirsty,’ says the nurse. I wonder if they laugh at the patients, who come in so brave and ignorant. None of us thinks that the complication rate applies to us.

The visitor’s idea of hospital is different from the patient’s idea. Visitors imagine themselves trapped in that ward, in that bed, in their present state of assertive wellbeing. They imagine being bored, but boredom occurs when your consciousness ranges about looking for somewhere to settle. It’s a superfluity of unused attention. But the patient’s concentration is distilled, moment by moment: breathing, not being sick, not coughing or else coughing in the right way, producing bodily secretions in the vessels provided and not on the floor. The visitor sees the hospital as needles and knives, metal teeth, metal bars; sees the foggy meeting between the damp summer air outside and the overheated exhalations of the sick room. But the patient sees no such contrast. She cannot imagine the street, the motorway. To her the hospital is this squashed pillow, this water glass: this bell pull, and the nice judgement required to know when to ring it. For the visitor everything points outwards, to the release of the end of the visiting hour, and to the patient everything points inwards, and the furthest extension of her consciousness is not the rattle of car keys, the road home, the first drink of the evening, but the beep and plip-plop of monitors and drips, the flashing of figures on screens; these are how you register your existence, these are the way you matter.

For the month of July, my world is the size of the room that, as an undergraduate, I shared with a medical student, a box of bones under the bed and a skull on our shelf. I think of the long wards of the hospitals I visited as a child, fiercely disinfected but with walls too high to be cleaned properly: those walls receding, vanishing into grey mist, like clouds over a cathedral. Wheezing and fluttering, or slumped into stupor, my great-aunts and uncles died in wards like those. Wrapping and muffling themselves, gazing at the long windows streaming rain, visitors would tell the patient: ‘You’re in the best place.’ And as the last visitor was ushered out on the dot, doors were closed, curtains pulled, and the inner drama of the ward was free to begin again: the drama enacted without spectators, within each curtained arena a private play, and written within the confines of the body a still more secret drama. Death stays when the visitors have gone, and the nurses turn a blind eye; he leans back on his portable throne, he crosses his legs, he says, ‘Entertain me.’

A few days after the surgery I take a turn for the worse. No human dignity is left; in a red dawn, I stagger across the room, held by a tiny Filipina nurse, my heart hammering, unspeakable fluids pouring from me. Hours later, when my heart has subsided and I am propped up and reading the Observer, I think this moment is still happening, still being enacted; I live in two simultaneous realities, one serene and one ghastly beyond bearing. When my dressings are stripped off I bob up my head to look at my abdomen. My flesh is swollen, green with bruising, and the shocking, gaping wound shows a fresh pink inside; I look like a watermelon with a great slice hacked out. I say to myself, it’s just another border post on the frontier between medicine and greengrocery; growths and tumour seem always to be described as ‘the size of a plum’ or ‘the size of a grapefruit.’ Later a nurse calls it ‘a wound you could put your fist into’. I think, a wound the size of a double-decker bus. A wound the size of Wales. It doesn’t seem possible that a person can have a wound like that and live, let alone walk about and crack jokes.

On 12th July I am attached to a small, heavy black box, which will vacuum ou

t the cavity and gradually close its walls. A clear tube leads from beneath my dressings into the box, and the box is plugged into the wall. It snorts like an elderly pug, and bloody substances whisk along the tube. Through August, as the weather warms up, it will smell like a wastebin in a butchery, and flies will take an interest in it. I can unplug myself for a few minutes, but reconnecting to it is painful. There is a shoulder strap, for use by the robust, those on their way to mending, but when I get out of bed I carry the box before me in both hands. Its ferocious gasping will soon start to suck the dressings inside the wound, and sometimes in the night it will whistle and cheep, to continue until a keeper comes with knowledge of its workings.

Until now I have been giddily optimistic, but the arrival of the black box sobers me. It takes around an hour each time to dress my wound. During one session, a subdued screaming comes from another room; I hope it is from another room. I have an aversion to expressing pain, an aversion which in a hospital is maladaptive. You should squeal, flinch, object and ask for relief. But I have a rooted belief that if you admit you are hurting, someone will come along and hurt you worse. As our parents used to say, ‘I’ll give you something to cry for.’ My brain seethes with ideas, so when my wounds are dressed I go limp as an old sheet and start novels in my head; one can always start them. My favourite story is set in the Raj and its heroine is called Milly Thoroughgood; she is something between Zuleika Dobson and Becky Sharp. The beauty of a novel in the head is that you can run to stereotype: the blushing young clerk with a conscience and secret lusts, the charming military blackguard with the wrecked liver. The novel is composed in elaborate Jamesian circumlocutions, and I breathe along with the punctuation. Sometimes I smile at Milly’s scathing comments to her beaux. The nurses think I’m gallant, a tractable patient; they don’t know I’m in another country. My least favourite nurse huffs and puffs while he is doing the dressing, and sometimes kicks the bed, as if startled to find it there. My abstraction allows the staff to talk across me: ‘Kim said that David should apologise to Jules, but I said he should apologise to Samira, and she said he should apologise to Suzanne, and Suzanne said she wasn’t going to apologise to anyone, ever. But I think they should all apologise to me.’

Every Day Is Mother's Day

Every Day Is Mother's Day An Experiment in Love

An Experiment in Love Wolf Hall

Wolf Hall A Place of Greater Safety

A Place of Greater Safety Vacant Possession

Vacant Possession The Giant, O'Brien

The Giant, O'Brien Beyond Black

Beyond Black Ink in the Blood: A Hospital Diary

Ink in the Blood: A Hospital Diary The School of English

The School of English Giving Up the Ghost

Giving Up the Ghost The Mirror and the Light: 2020’s highly anticipated conclusion to the best selling, award winning Wolf Hall series (The Wolf Hall Trilogy, Book 3)

The Mirror and the Light: 2020’s highly anticipated conclusion to the best selling, award winning Wolf Hall series (The Wolf Hall Trilogy, Book 3) Fludd

Fludd Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street Learning to Talk

Learning to Talk How Shall I Know You?: A Short Story

How Shall I Know You?: A Short Story A Change of Climate

A Change of Climate Bring Up the Bodies

Bring Up the Bodies The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher: Stories

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher: Stories Beyond Black: A Novel

Beyond Black: A Novel Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies

Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies Bring Up the Bodies tct-2

Bring Up the Bodies tct-2 Ink in the Blood

Ink in the Blood The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher Eight Months on Ghazzah Street: A Novel

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street: A Novel How Shall I Know You?

How Shall I Know You? A Change of Climate: A Novel

A Change of Climate: A Novel The Giant, O'Brien: A Novel

The Giant, O'Brien: A Novel Fludd: A Novel

Fludd: A Novel A Place of Greater Safety: A Novel

A Place of Greater Safety: A Novel An Experiment in Love: A Novel

An Experiment in Love: A Novel